As Macedonians throughout the world unite in a moment of silence and light a candle to remember those who have suffered the brutality of the Greek state for the last 150 years and commemorate the Macedonian Genocide, we, at UMD wanted to share this very touching and authentic story by Adelaide-based Australian-Macedonian Helen Manou about her mother who was one of the “maiki” during the Greek Civil War. Her family history is part of our collective narrative as Macedonians, that we should all treasure and hold onto dearly.

Despite all the adversities that Helen’s mom faced at a young age, she found the strength, resilience, and courage to move forward, even if not in Macedonia. This is an important lesson for all of us, especially younger Macedonians in the diaspora. It is also what motivates the global UMD family, that regardless of the challenges past and present, we continue to advance our Macedonian legacy and the interests of Macedonians with a passion.

——–

What does it mean to be a mother (“maika”)? It matters not what the dictionary meaning says it is in its purest form. For the Macedonian “maika” (mother) it did not necessarily mean birth mother but also encompassed a woman whose role it was to take care of the children entrusted to her during the Greek Civil War from 1946 – 1949, to lead them to safety to various countries throughout Europe to escape the ravages of this particular war.

My mother Sofia Konstantinouska was 18 years old when she was asked by the village elders to become a “maika” and was tasked with the well-being of a group of children and to lead them to safety over the border. She was responsible for ensuring they were fed, clothed, bathed, and taught how to look after themselves and others. Some of these children were young and aged between 3 and 11 years, and had been taken away from their own mothers and fathers and given over to the authorities and subsequent care of the “mothers” (maiki).

Mum had earned the reputation of being a strong and able individual. She had looked after the family with her mother after her father had suffered a complete nervous breakdown, after the shame of being deported from America for being an illegal immigrant. He had gone to Canada on “Pechalba” and the situation was not ideal and decided to cross the border into the USA. However, some of his compatriots who had been in the army with him and who were envious of his standing as a doctor’s assistant had reported him to the authorities.

It had been a difficult time for the family and mum had been constantly taken out of school to care for her father and younger siblings. The teacher would admonish my grandmother because Sofia was a particularly bright student. However, my grandmother could not manage on her own.

Initially, Romania agreed to take the bulk of the Macedonian children and other vulnerable people. My mother’s first-cousin Sondra was one of the approximately 10,000 children and older people taken in by Romania. Later, Poland also agreed to take the refugees as well. Members of our immediate family were taken to Poland, Romania, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary.

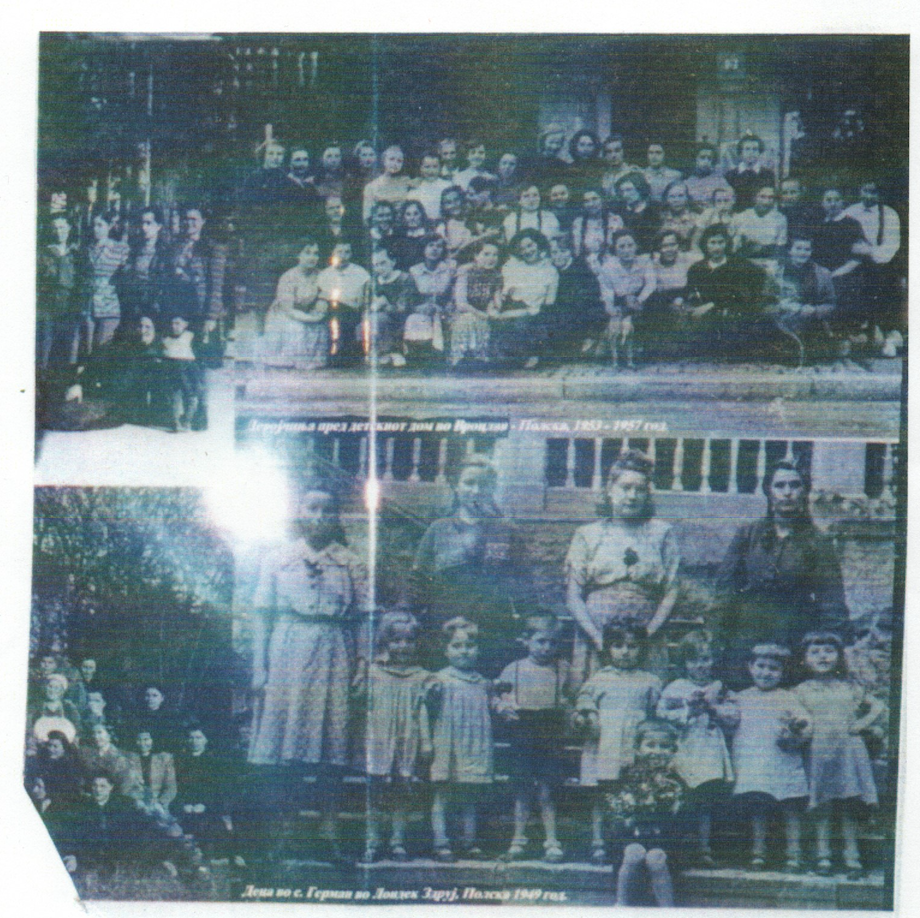

My mother had been to Czechoslovakia (as it was then known) and also to Romania for a brief time, but the majority of her time was spent in Poland where she lived in the Children’s Home in Plakowice.

Some of these women were trained to teach lessons to the children and my mother was one of them. She was schooled in the Macedonian language prior to leaving Greece, as it was her birth language and she had been taught how to read and write by her father. She taught this language to her students at the Children’s home as well as other lessons.

When Greece annexed the Aegean part of Macedonia, the Greek Government of the time wanted the population to become “Hellenised” and the Macedonian language was banned from being spoken. The Macedonian population had their names changed to Greek names and their villages changed to Greek-derived names. My mother’s village of Medovo became Miliona, sweet as honey (in name only). The people had curfews placed on them and there was a price to be paid if one was heard speaking their own language.

My mother had apparently told her class at school that her father had been reading to them at home in Macedonian. The teacher, who was coincidentally a friend of my grandparents, warned them that they could get into trouble if this had been divulged. Mum was sanctioned and told never to speak of the Macedonian books again.

After mum’s training, she and a group of other women with their allotted children crossed the border into the former Yugoslavia. Initially, mum was stationed at the border and helped the children get on trains which would take them to their designated refugee camps and then transported to various Eastern Bloc countries throughout Europe who had agreed to take them. She would tell us how they were deloused and had their plaited hair untangled and DDT sprayed over them.

When mum was at the border, her younger brother Pande and sister Sondra were on a train with her and it had stopped at a station where a barrow of bread had been placed there for the children. Mum and another young woman who was breast-feeding her small child saw the bread barrow and the young woman took her child off her breast and gave the baby to her small daughter to hold.

Mum and the young woman ran onto the platform to get the bread for the starving children. As they were collecting the bread in their arms, the train took off and both mum and the young woman were left stranded. They were both screaming and incredulous at this circumstance. Mum said that the shrieks of the woman would remain etched eternally in her psyche.

Everywhere mum went she would ask the authorities to reunite her with her siblings. One of the officers who was responsible for the children’s care asked my mother why she was so insistent on asking this question. Mum pulled out a letter from her father and gave it to him to read. In the letter, Dedo Risto, wrote how ashamed he was that she had abandoned her brother and sister. The officer in charge with tears in his eyes told my mother he would do all that he could to reunite her with her siblings. This eventuated when my Teta (aunt) Sondra and Vouche (uncle) Pande were sent to the Children’s Home in Plakowice, Poland where mum worked.

It came to bear that both my mother’s family and also my father’s family ended up being refugees to Poland. This is where my parents met and married. My father who was a partisan and endured two operations in 24 hours in Albania to save his leg, had been brought to Poland on a hospital ship after being resident in the Albanian hospital for two years.

My grandmother who was all alone in German (Agios Germanos) in the Prespa region had also been evacuated to Poland and got wind that her son was arriving and sought him out. She sat vigil next to dad’s bed on his arrival. When dad awoke and took in his surroundings, he was shocked to see his mother at his side. They embraced and filled each other in on the intervening years and what had happened to the family. It was then that my father vowed that he would never leave his mother again.

My Uncle Stojan Kolachkov and his wife Elena had been killed in the Greek Civil War and my Aunty Fana (Fay) had been imprisoned at the age of 16 years for allegedly aiding the partisans, which she strenuously denied. She was brought to trial and found not guilty together with several other girls from the jail and released after 18 months. However, they had nowhere to go because most of the population had fled over the border and the roads to their villages were blocked. They were taken in by the Magistrate’s family who had tried them and looked after by them until it was safe for them to return to their villages sometime later.

My grandfather Vasil Kolachkov from German had left his native Macedonia and had come to Australia in 1930, and was apart from his family for 26 years. However, in 1955, our family was reunited in Adelaide, South Australia, and lived together in a three-generational household.

Sofia Kolachkov died on 25 September 2016. Our family would constantly tell us about the war years and all they endured during this turbulent and terrible time. Mum was my brother John’s and my birth mother, but she was also a “maika” to innumerable children in her care and earned the title of “maika” for the exemplary care she showed to all her children.

My husband Arthur and I were lucky enough to attend the Deca Begalci 50th anniversary in Skopje in 1998 because mum had severe rheumatoid arthritis and could not attend. There was a photographic exhibition at the Railway Station building. My mother’s photograph was there showing her with her small charges in front of her, together with other “maiki”. A television reporter asked me why I was crying, and I told him that the young woman in the photograph was my mother.

Mum told me that she would have to console children whose parents had been killed or died throughout her time at the Children’s Home. She had to be their teacher, “maika,” and friend. We are proud of her tenacity at such a young age.

Mum’s favourite saying was, “the truth, like oil, will rise to the top of the water”. My hope is that this truth is never forgotten.

Rest in peace mum from all your children.